Laying Stones for the Cathedral: The Sacrificial Love of the Missionary and the Mother

Written by Megan Keyser

“But the Cathedral is not for us, Father Joseph. We build for the future…”

Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop, 234

Each time I pick up a new novel, I am struck by how difficult it can be to acclimate myself to the unaccustomed literary landscape. Familiarizing oneself with new characters, settings, and themes can be challenging. Additionally, writing styles can be jarringly different from one author to the next, and the dissimilarities can leave us feeling dizzy, confused, or disoriented. As I trudged along through the sleepy and slow-moving opening chapters of Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop, I felt disengaged and subsequently unmotivated by this selection—so foreign to my literary sensibilities and typical longings for witty banter and intriguing plot lines. Yet, as the novel serenely unfolded, I realized that this series of quiet, almost picturesque vignettes was a disarming invitation to examine the unforeseen depth of a simple yet moving, all-encompassing surrender to the Divine Will prompting a new understanding of love.

Cather’s work chronicles the experiences of historical figures Archbishop Jean Marie Latour and his fellow missionary and dear friend, Father Joseph Vaillant, as they sought to evangelize the American southwest in the 1800s. The pair lived a life of inspiring zeal and solidarity in their mutual pursuit of serving God and neighbor: a quest nurtured and augmented by their intimate friendship. As we embarked on another year of reading with the Well-Read Mom, discussing great ideas and questions with friends, I felt stirred by the importance of companionship in the novel. Both men were irrefutably vital in promoting the sanctification of the other. Without Latour’s quiet diplomacy and prudent counsel, Father Vaillant smothers his missionary calling with his emotional trepidation in leaving his family in France.

Had that happened, the New World would have been deprived of this saintly priest’s tenacious spirit and ardent fervor. Yet with equal dependency, the Archbishop drew from his friend’s zeal and passion, channeling Vaillant’s strength to meet the demanding and sometimes perplexing responsibilities he faced as Bishop and, later, Archbishop. As evidenced in the novel, our gifts and talents can only blossom through the careful pruning and cultivation we experience through the influence, encouragement, prayers, and counsel of others. Though it may seem paradoxical to the modern mindset, in which staunch individualism and personal autonomy reign, if we are to become the individuals God has destined us to be, we must depend upon our fellows. We were designed for the intimacy and dependency of the human relationship to reach our full flowering as individuals.

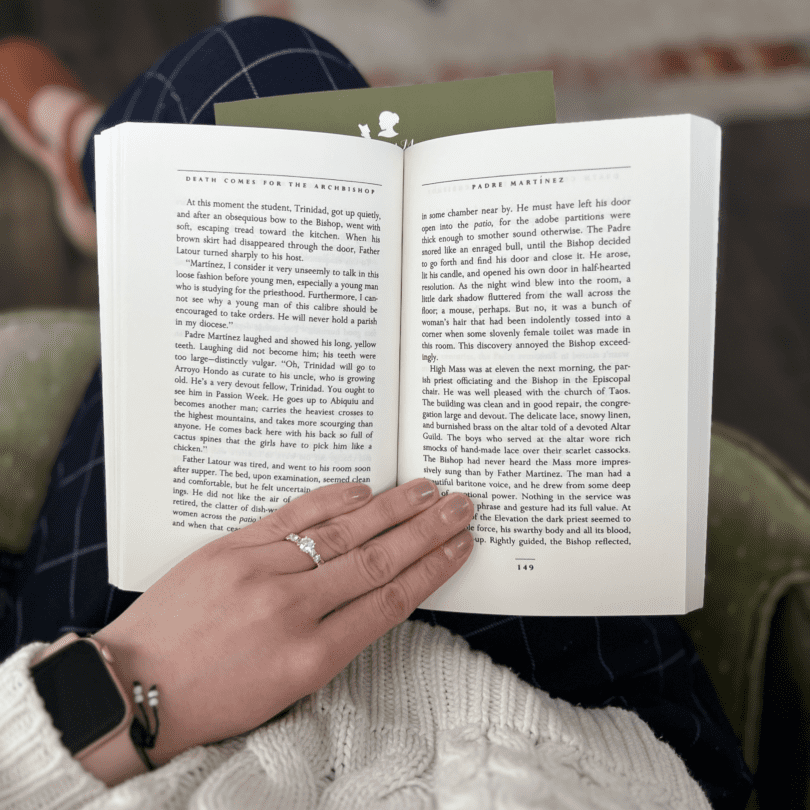

We witness the impact of friendly exchange and encouragement near the novel’s beginning. The two priests enjoy a rare but cherished moment of camaraderie and pleasure at Christmas dinner together. During mutual pondering and conversation, Father Joseph openly objects to the then Bishop’s impulse to fully pursue his missionary work throughout his extensive and undefined diocese, imploring his superior to focus his attention on Santa Fe: “But no farther, Jean. This is far enough. Do not drag me any further…There is enough to do here…. I have made a resolve not to go more than three days’ journey from Santa Fe for one year” (page 40). With a knowing smile, the Bishop replies to his friend: “And when you were at the Seminary, you made a resolve to lead a life of contemplation” (40-41). This unobtrusive interchange, so simple yet ripe with significance, resonated within my heart and caused me to reflect on my vocational journey as a mother. Recollecting my maternal path, I often laugh at the halting yet irresistible progression of surrendering my heart to a noble cause. I remember a teenage girl who dreaded the potential agonies of future childbirth, unable to imagine such a physically demanding surrender to love. Yet despite her aversion, only a few years later, this same young woman found herself in the throes of labor, gritting her teeth as she gave her all for the fruit of the love she shared with her husband. So many failures and moments of physical, emotional, and even spiritual anguish ensued in the following years as her family and inherent responsibilities grew. Yet, with each small, faltering step toward love, she found her strength and willingness to surrender, expand, and mature. I know my experience is hardly singular but is felt by countless mothers, who, in relinquishing themselves, their comforts, and their desires in submission to something greater than themselves, find a slow but undeniable growth toward a more perfect and sacrificial love.

In a testimony to the continual and transformative power of such love, by the end of the novel, Father Joseph, aglow with ardor for the “lost children of God,” begs the Archbishop to send him even further into Arizona to offer “[a] word, a prayer, a service” to liberate “souls in bondage” (207). While he initially recoiled at the habits, customs, and manners of the Mexican and other Native peoples, Father Joseph finds what once seemed repugnant to him has become his joy. He has learned to love fully and deeply, and in this sacrificial devotion, he has ironically uncovered true happiness and fulfillment. Similarly, the Archbishop, when returning to his homeland of Clermont, France, though appreciative of its beauty and nostalgia, finds “himself sad there,” and only then fully recognizes the power of his heart’s mission and hastens back to fulfill it: “He did not know just when it had become so necessary to him, but he had come back to die in exile for the sake of it” (273).

Marriage and motherhood, like missionary work, are like an odyssey into the unknown. Turning our back on things familiar, we forsake the comforts and customs of the family and home we have always known to cultivate a new family alongside our husbands. We undertake struggles and face challenges all for the sake of the other. This love bears fruit: either in the form of biological children—the physical manifestation of love—or in the birth of spiritual and emotional heirs (adopted children, students, neighbors, and friends), whom we rear, mentor, and guide with deep affection and devotion. This openness to love can be excruciating—as love continually exposes our vulnerabilities—and we frequently find ourselves battling the isolation of familial discord, facing the numbing, monotonous pain of daily strife, or even confronting the heart-wrenching agony of pain, loss, and tragedy. But perhaps the most significant hurdle of all is the knowledge that we, like the Archbishop and Father Vaillant, can never fully expect what is to come but must bow in humble obedience and surrender to Divine Love, no matter the personal cost: “But it was the discipline of his life to break ties; to say farewell and move on into the unknown” (246).

Indeed, it is hard to see the glory in the succession of humble assents that comprise a life of faithfulness and generosity. When we choose to share our lives with others, to abandon ourselves to that “Unknown,” we are often called to exhaust and expend so much of ourselves that we wonder what we will leave behind of worth. This pondering is even more acutely felt in our modern world of shiny exteriors and glittering accomplishments, and we tend to question our personal significance and individual contributions. In a pivotal moment of discouragement and despair, the Archbishop, deprived of the companionship of Father Vaillant and bereft of spiritual consolation in his prayers, begins to question his life’s efforts as he examines the meager strides he has made in fostering the Catholic Faith in his fledgling diocese: “His work seemed superficial, a house built upon the sands” (211). Yet his providential encounter with an enslaved and abused woman, whose passion for the Faith staunchly withstood the intense sufferings of her life, rekindled his hope: “He was able to feel, kneeling next to her, the preciousness of the things of the altar to her who was without possessions; the tapers, the image of the Virgin, the figures of the saints, the Cross that took away the indignity from suffering and made pain and poverty a means of fellowship with Christ” (216-217). As mothers and fathers tackling the ordinary works of child-rearing and home-making—changing seemingly limitless diapers and overseeing mountains of schooling, preparing hurriedly eaten meals and mowing the unrelenting lawn, scrubbing floors with a sense of futility and tending both to capricious needs of tiny people and the mysterious hearts of teenagers and young adults—we often feel as though we are building a “house upon the sands.” In these moments of discouragement, we fail to recognize what we are ultimately crafting: shaping worlds and enriching minds, refining tastes, and cultivating virtue. Like Archbishop Latour and Father Vaillant, we design cathedrals and forge missions, but we sometimes do not recognize the growing splendor in the simple “stones” we are laying. Every once in a while, and perhaps increasingly, as we abandon ourselves to sacrificial love, the veil is lifted, and we are miraculously gifted with an understanding of the miracle we are helping to create: “Where there is great love, there are always miracles… One might say that an apparition is human vision corrected by divine love… The Miracles of the Church seem to me to rest not so much on faces or voices or healing power coming suddenly near to us from afar off but upon our perceptions being made finer so that for a moment, our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always” (50).

As the novel concludes, it is easy to marvel at the accomplishments of these two pioneers for Christ, who sacrificed so much to bring the Catholic Faith to hungering souls. Yet the tales that comprise their story are, for the most part, not shockingly fabulous or riveting. They seem ordinary, though undoubtedly challenging. Their earthly pilgrimage seems more like a persistent plodding of barely perceptible advancement—both for themselves and for the souls they shepherd—than a glorious vision of miraculous and instantaneous spiritual transfiguration. Perhaps this dogged commitment to the Truth and their calling, even when they did not feel like pursuing it and even when it had lost its novelty or spark, offered me such tangible hope in my own ordinary and sometimes defeating duties as a wife and mother. Latour and Vaillant’s willingness to endure so much trial was undoubtedly inspiring, but even more captivating was the acknowledgment that their initial, and even persistent, hesitations, worries, fears, frustrations, and hopelessness in their respective journeys did not ultimately impede their obedience to God and His Will. Theirs was not a story embellished with success after success but a tale of two souls—despite frequent feelings of inadequacy, uncertainty, and irresolution—who consistently placed their humble efforts upon the heavenly altar: small tributes of fidelity, steadfastness, and hope, not wrapped in grandeur, but nestled in unassuming beauty because of the love that prompted their pains.

As we ponder these moments in the lives of missionaries from so long ago, I hope the veil that often obscures our proper vision of things will rise, allowing us to see the true dignity and magnificence of our actions, however paltry they initially appear, when illuminated by love. During these moments of simplicity, His greatness shines brightest because His love has been distilled to its most concentrated form, unadorned by deception, and found in the emptying of self for others. We encapsulate greatness in simplicity, and it is through Divine Love that we can learn the way.

About Well-Read Mom

In Well-Read Mom, women read more and read well. Our hope is to deepen the awareness of meaning hidden in each woman’s daily life, elevate the cultural conversation, and revitalize reading literature from books. If you would like to have us help you select worthy reading material, we invite you to join and read along with us. We are better together! For information on how to start or join a Well-Read Mom group visit our website wellreadmom.com