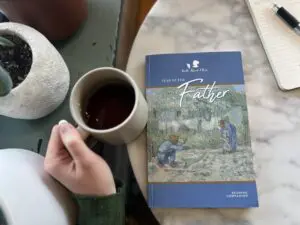

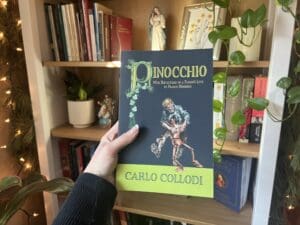

The Well-Read Mom edition of Pinocchio With Reflections on a Father’s Love is a rare gem because we are presenting Carlo Collodi’s original tale alongside extensive reflections made available in English for the first time by Franco Nembrini. Nembrini’s reflections are essential to what Well-Read Mom desires to highlight about fatherhood, freedom, identity, and love in Pinocchio. Having these reflections to draw upon will add to our understanding of the text, deepen our discussion, and provide a true education for our hearts.

As I look back on several years participating in Well-Read Mom, (since the Year of the Friend!) I am so happy that in every book list there has been at least one book that stretches my mind.

As we reflect this year on the vocation of fatherhood, we see that authentic fatherhood – and by extension, motherhood – consists in the willingness to offer oneself, most especially to those souls placed within one’s authority and care. And perhaps, in light of our reflection on the life of Saint Francis, we can even further be gladdened by the vital link between parenthood and sacrificial, sanctifying love.

He is one of the most readily recognizable saints of all time: his likeness graces many a garden, he is beloved for his appreciation of the natural beauties and the majesty of God’s animal kingdom, and his spirit of gentleness is universally lauded by both secular and religious camps. Yet, for all his cultural notoriety and esteem, how many of us truly know the person of Saint Francis of Assisi?

Come as You Are Written by Susan Severson The dinner plates had barely been shoved into the precariously full dishwasher before I finally faced the question: should I go to Well-Read Mom tonight? It certainly wouldn’t be convenient. We were in the midst of moving from our home of nine years to one that would…

The Old and the New: Rediscovering Literature Through Well-Read Mom Written by Nicki Johnston I started a new Well-Read Mom group for women in my parish this year. Inevitably, I received inquiries about the need to pay for a booklist, allowing me to articulate the many ways Well-Read Mom has enriched my life during the…

Pinocchio: With Reflections on a Father’s Love has been a great surprise for me. Many people in America are familiar with the Disney version of this story, which pales in comparison to the depth of Collodi’s original. However, the commentary in this special edition has helped me as much, if not more, than the story itself. This edition has enabled me to live with greater awareness, teaching me how to approach my work at home with deeper gratitude and appreciation.

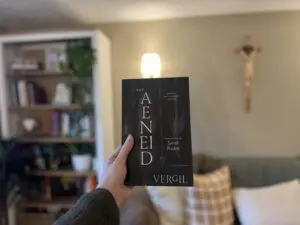

The Restoration of Culture Through Literature and Prayer Written by Christina Mermis In an essay entitled “The Importance of Virgil”, my favorite author and educational reformer, John Senior, wrote, “If I succeed in giving anyone even the slightest glimpse into the rich treasure of Virgil, I shall have made my case for the restoration of…

At the behest of Well-Read Mom, several faithful, tome-toting women are meeting to discuss Vergil’s Aeneid at their book club meetings this month. While some of us may be Latin scholars, most are out of our comfort zones.

I attended the Well-Read Mom “Awaken Your Heart” conference in Milwaukee earlier this month. There were so many beautiful things about the weekend, not the least of which was being with many other like-minded women who were reading the same thing. During this conference, many conversations were about The Aeneid. Being right in the thick of this book myself, I couldn’t help but connect much of what I heard from the speakers to Virgil’s poem.