With Reins in Our Teeth: How Boldness is Both Necessary and Attainable

Written by Megan Keyser

“What is ‘true’ grit, anyway?”

“Is it something we’re born with?”

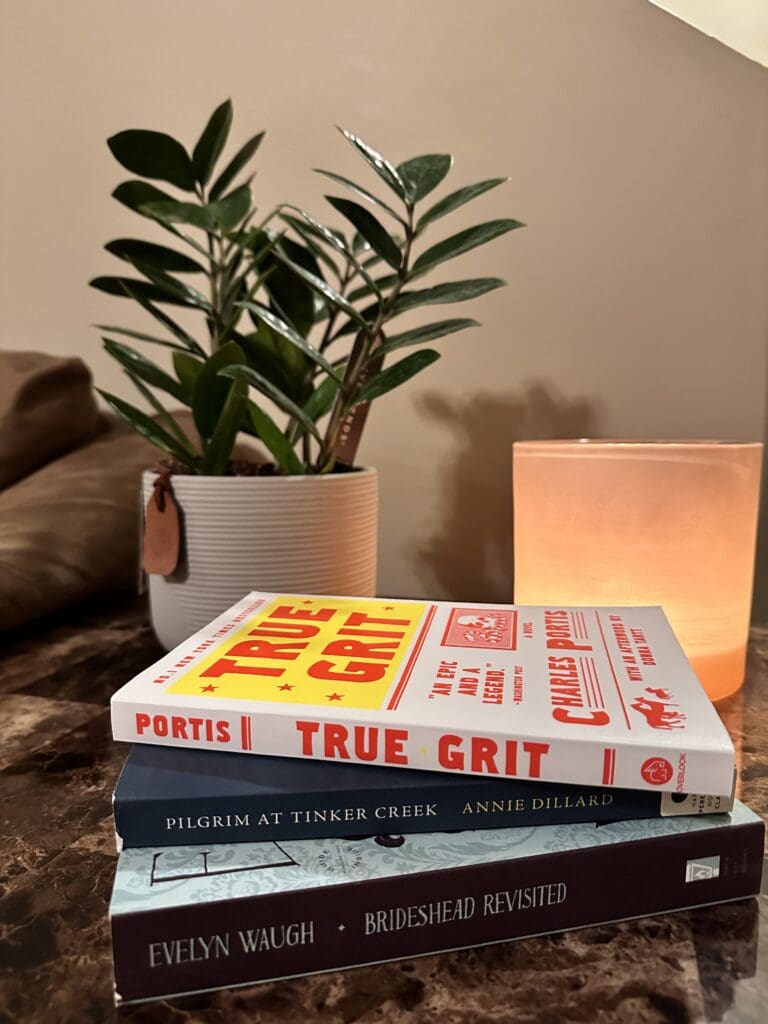

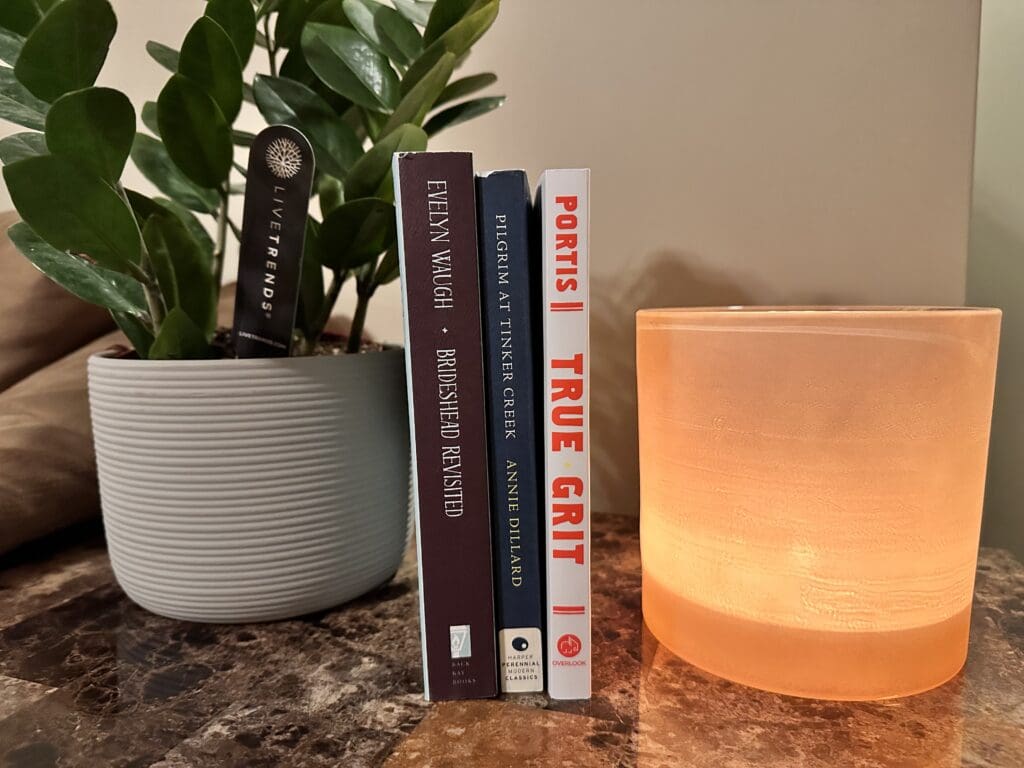

Well-Read Mom’s Year of the Seeker Reading Companion poses these questions for discussing Charles Portis’ novel True Grit. My group thoroughly pondered these queries as we considered the work. True Grit offers an exciting portrayal of the American West, told through the perspective of the indomitable Mattie Ross, a fourteen-year-old girl of considerable gumption who sets out on an expedition to avenge the murder of her father. The tale is replete with vivid depictions of late nineteenth-century life, featuring startling brutality, but also laced with comic character portrayals and amusing asides given directly—and very bluntly—by pragmatic and forthright Mattie.

Before venturing on her vengeful quest into the Indian Territory, Mattie sought the assistance of a U.S. Marshal, choosing, among other candidates, Rooster Cogburn, after he was candidly described as “a pitiless man, double-tough, [for whom] fear don’t enter into his thinking” (page 29). Later, when Mattie first meets Rooster, the annoyed Marshal asks why she had sought him out, to which Mattie frankly responds: “They tell me you are a man with true grit.” Mattie equated “true grit” with hard-hitting, robust fearlessness—qualities she and Rooster continually exhibit throughout the work.

Again and again, when met with opposition on her journey, Mattie shows the depth of her resolve by staunchly pursuing her aim—despite dubious reactions or outright disbelief from others. In a moment that both epitomized Mattie’s “grit” and solidified Rooster’s quiet esteem for the spirited girl, Mattie plunges herself and her horse, Little Blackie, into a frigid river, in hot pursuit of Rooster and the Texas Ranger, LaBoeuf: “I aimed for the place, going like blazes across a sandbar. I popped Blackie all the way with my hat as I was afraid he might shy at the water and I did not want to give him a chance to think about it” (109).

What stands out particularly is the single-minded focus of her vision: heedless of the danger, she races directly where the “river [was] the deepest and…the current [was] swiftest and the banks steepest, [though] these things did not occur to [her] at the time; shortest looked best” (109). Without fear, anxiety, or hesitation, Mattie dives headlong into peril—compelled by some inward force to face danger to achieve something she deems necessary.

Similarly, Rooster exhibits a dauntless sense of conviction. No fearsome criminals or formidable odds could impede his resolve, and he doggedly confronts danger without hesitation. When LaBoeuf pointedly asks Rooster whether he plans to run rather than face Ned Pepper and his gang, Rooster “turn[ing] a glittering eye on him [replied] ‘I aim to do what I come out here to do'” (138).

If “true grit” is an unflappable determination in the face of any circumstances, however horrific, challenging, or dire, the question remains: is this a natural gift or an attainable virtue? Many of us might like to equate this type of tenacity with a personality type—a type of bravery beyond the scope of “ordinary” people—because it exonerates us from demonstrating that level of courage or resoluteness ourselves. We look, wonderingly, at people who readily charge into battle or unhesitatingly risk themselves to save another or unflinchingly stand up to injustice. We doubt our own ability to emulate them, saying such people are naturally gifted with fearlessness, and we are not.

Certainly, there exist individuals who, even from their earliest moments, seem to possess an audacious disregard for danger—those who bravely confront challenges from the childhood playground onward with a natural ease. But for most “brave” people, the ascent toward courage has been a gradual journey in which countless small challenges, valiantly met, have served as stepping stones in cultivating truly noble and indisputable heroism.

When reading in-depth histories of saints and martyrs, one finds that the almost fantastical representations we read as children (frequently provided in short paragraph summaries of a holy individual’s life) leave so much out of a saint’s arduous and painstaking journey in acquiring epic devotion. Martyrologies sometimes zoom so rapidly to the heights of holiness and self-sacrifice that we are bereft of the humanizing details—the tiny conquests over selfishness, temptation, and ease—that enabled these saints to uncompromisingly, joyfully, and whole-heartedly give themselves to an otherworldly aim: namely, unquenchable love of God and neighbor.

And that is really what is at the heart of authentic courage and true grit. It is that sense of purposefulness beyond oneself and narrow personal interests that prompts us to act nobly in the service of something or Someone greater. For Mattie, that purpose was securing justice—a justice she recognized would not be achieved without her intervention—for her father’s murder. For Rooster, that resolution ultimately ended in giving his all to save Mattie, whom he had come to respect, admire, and even love with a paternalistic tenderness, however inconspicuous beneath a gruff and crotchety veneer.

Our purpose should be rooted in a life of ardent, self-giving love. The feminine quality of generosity is one from which bravery can be poignantly revealed. Our capacity for self-giving, exemplified in our biological and spiritual fruitfulness, directs our daily actions and provides spiritual endurance for life’s challenges. That natural gift, however, must be coupled with the cooperation of our wills—a resolve that requires continual renewal. Our souls are transformed with every triumph, however seemingly insignificant, over temptation, anger or impatience, laziness or disregard. We are becoming women of “true grit.”

We need toughness to be holy. As Mother Angelica, founder of EWTN, used to quip, “Holiness is not for wimps.” Not all of us are called to publicly face injustice or fight in actual battles. Still, each of us is called to stand boldly against evil and selfishness—chiefly the self-centered tendencies that arise in our hearts—and to endure the crosses and trials unique to our lives with grit and grace. And we can discover that resoluteness, that grittiness to withstand hardships or maltreatment or irritations by grounding ourselves in purpose: the type of purpose that gives significance to our sufferings and almost impels us to choose the Good.

Toward the novel’s conclusion, while talking to Mattie, Rooster related his experience of going up against a posse of seven armed men by himself:

“I turned [my horse] around and taken the reins in my teeth and rode right at them boys firing them two navy sixes I carry…I guess they was all married men who loved their families as they scattered and run for home” (146). When pragmatic Mattie expressed her disbelief, Rooster replied: “We done it in war. I seen a dozen bold riders stampede a full troop of regular cavalry. You go for a man hard enough and fast enough and he don’t have time to think about how many is with him, he thinks about himself and how he may get clear out of the wrath that is about to set down on him” (146).

We may sometimes feel overwhelmed by the number of evils surrounding us or the sufferings that beat down on us. Still, let’s call upon our sense of purpose and vision—a purpose shaped by seeking truth and beauty. We can continually accept the small challenges that beset us each day. We might even be surprised by the true grit within us.

About Megan Keyser

Originally hailing from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Megan is a 2006 Hillsdale College graduate with a degree in Classical Studies. These days, Megan thrives on the challenges and joys of her role as a Catholic, stay-at-home mother, who heads a chapter of the Well-Read Mom, dabbles in social commentary and other writing pursuits, and advocates for the pro-life cause. Despite the inevitable chaos of large family life, Megan is thankful for her lively brood and relishes juggling household responsibilities, babies in diapers, and, of course, a good book. She resides in Noblesville, Indiana, with her husband, Marc, an engineer in the energy industry, and their ten children: five sons and five daughters, ages 15 years to 6 months old.

About Well-Read Mom

In Well-Read Mom, women read more and read well. Our hope is to deepen the awareness of meaning hidden in each woman’s daily life. We long to elevate the cultural conversation and revitalize reading literature from books. If you would like us to help you select worthy reading material, we invite you to join and read along. We are better together! For information on how to start or join a Well-Read Mom group visit our website wellreadmom.com