Severity As Merciful As Love

Written by Megan Keyser

As a child and later, as a teenager, I wasn’t especially known for my ability to withstand pain or discomfort bravely. When met with injuries or inconveniences, my tendency was more toward melodramatic soliloquies or tearful outbursts than toward a valiant welcome of the suffering at hand. Motherhood, however, catapulted me into a world brimming with countless tiny frustrations and considerable heartache. Though I still find myself grumbling under the weight of various burdens—some light, some significant—I believe this vocation was just what was needed to prune away the more thorny and unpalatable aspects of my character. One might say that motherhood, and its characteristic struggles, has been a “Severe Mercy” for me and an insight into genuine love.

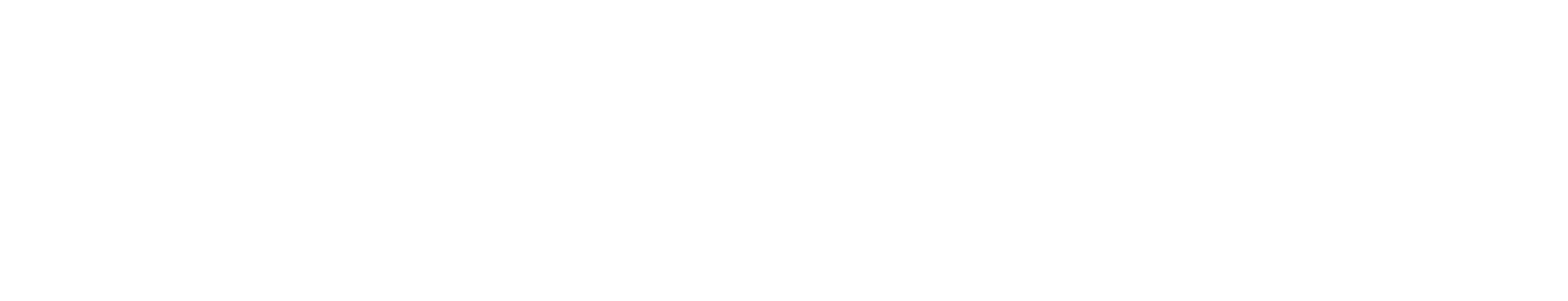

But what is a “Severe Mercy”? How can anything as sweet as mercy be coupled with severity? A Severe Mercy: A Story of Faith, Tragedy, and Triumph, by Sheldon Vanauken, chronicles the enthralling love affair of the author and his late wife, Davy, and their arduous descent into sorrowful loss. The book attempts to reconcile suffering with joy and bitterness with grace.

The memoir recounts the beautiful—almost dreamlike—connection between Vanuaken and his Davy: a love born out of shared devotion to beauty and wonder and a deep fidelity to each other. The soulful connection between the lovers is immediately captivating as they embark on a relationship almost unfathomably ardent—a romance marked by poetry and penetrating conversations, shared visions and common goals, and most notably, complete and utter devotion to love: “To hold her in my arms against the twilight and be her comrade for ever—this was all I wanted so long as my life should last…this consecration, this curious uplighting, this sudden inexplicable joy, and this intolerable pain” (29).

So sacrosanct was their adoration for one another that before marriage, the two young lovers created a code for maintaining and increasing their “inloveness,” a defense they referred to as The Shining Barrier: a structure of precepts intended to uphold full union between the two through unwavering trust and truthfulness, and mutual sharing. Nothing—no career, no children, no outside person, no hobby or interest—should ever threaten the splendor of their love, and therefore, all things submitted to the all-vital question: “What [would] be best for our love?” (41).

On the surface, such vigorous devotion appears both wondrous and laudable. As the work unfolds and their conversion to Christianity (largely encouraged by their friendship with C.S. Lewis) progresses, their relationship is examined in a new light. Yet for all the shining loveliness of their romance, the shade of self-love—an almost invisible, hidden selfishness—only became illuminated, ironically, in the heaviness of suffering.

Though gloriously vibrant, their love was jealous: dutifully guarded and turned inward upon itself, it stood as a shining idol to be revered rather than a life-giving outpouring of self for the service of God and others. No other individual could be fully permitted into this inner sanctum because offering unrestrained access to an “outsider” would force the surrender of what the lovers held most dear: the unfettered perfection of their “loveless.” So, despite the intoxicating beauty of their devotion, it remained spiritually, as well biologically, sterile because both God and children, particularly for Vanauken, needed to remain secondary to the interior paradise of the lovers’ hearts.

In an essay on the spirituality of Saint Francis de Sales, R.H.J Steuart writes “that in ordinary material (or at least non-spiritual) affairs we can usually attain excellence in any one direction only at the cost of sacrificing other possibilities of achievement” (Steuart, 310). Anyone who has opened themselves to the responsibilities of familial life will agree: the demands of parenthood exact a severe cost, not only upon worldly ambitions, but they can even encroach upon marital bliss.

Subsequently, with the creation of a family, the original relationship between husband and wife is radically changed as a matter of necessity. Trips to the emergency room, financial concerns, sleepless nights, heart-rending losses: these—and so much more—comprise the crucible of parenthood, and many times, husband and wife must sacrifice so much of their own relationship—freedom, exclusivity, serenity, and time—for the sake of the fruit of their union. But what if we reject the troubles associated with life-giving love to preserve the tranquil grandeur of our early romance? Should its beauty be preserved at the cost of generosity?

Radiant “inloveness” might be admirable, but Christ calls us to more: He commands us to a complete surrender of our whole selves, an offering up of all we love, out of love. The full flowering of charity necessitates the death of self: “Unless the grain of wheat falling into the ground die, itself remaineth alone. But if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit. He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world, keepeth it unto life eternal” (John 12:24-25).

In one of his letters to Vanuaken, C.S. Lewis chides the author for insulating the marital union at the expense of its potential flowering in children: “One Flesh must not (and in the long run cannot) ‘live to itself’ any more than the single individual. It was not made, any more than he, to be its Own End” (209). Marriage, therefore, however lovely, however sacred, remains a “glimpse…not a vision,” of the Eternal Beauty to which it should be directed (101).

How often do we create fortresses around idols: things, relationships, or even people that, while beautiful and admirable in their proper sphere, can potentially obscure the true End? We weigh the cost of giving with the toll it exacts on our happiness, and too often, we favor the path of contentment over the “Severe Mercy” of death: death to self, to contentment, to ease, to ambitions and hopes.

Parenthood always makes spiritual, physical, and emotional demands. I must confess, lately, my burdens have felt suffocating, and I have found myself openly wondering why God won’t just “give us a break.” Why does it have to be so very hard? But when I reflect on this memoir, it occurs to me that maybe my soul truly needs these exact sufferings to erode my own particular sins and shape me as God desires. Conceivably, each agonizing experience, heart-breaking anguish, and annoying vexation could be a lesson—if only we seek to look past the pain and discover how God might desire the suffering to refine us and turn our hearts toward Him. Instead of focusing on the severity of the suffering, maybe I should choose to focus on the merciful blessings of the spiritual transformation taking place in me—one grueling “Severe Mercy” at a time.

In moments of suffering, whether catastrophic tragedies or daily frustrations, we often question the goodness of God: how and why does He permit such grief and pain? But perhaps to erode self-love or “living to oneself,” the stretching—even shattering—of our hearts is required to enlarge them. Perhaps God, as a wise parent, knows that the only way our narrow loves can be sanctified is to dismantle the boundaries of our hearts by permitting sufferings, great and small, to shatter our illusions and redirect stubborn gazes toward Him. As Vanauken recognized, despite his grief, “It took [Davy’s] death, ironical as it must seem, to make me content in her turning her gaze from me to the eternal Fountain…a severe mercy [to] breach the Shining Barrier, and by breaching it, save that guarded love for the eternity it longed for” (216 & 219).

“It took [Davy’s] death, ironical as it must seem, to make me content in her turning her gaze from me to the eternal Fountain…a severe mercy [to] breach the Shining Barrier, and by breaching it, save that guarded love for the eternity it longed for.”

Sheldon Vanauken, A severe mercy

Megan Keyser

Originally hailing from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Megan is a 2006 Hillsdale College graduate with a degree in Classical Studies. These days, Megan thrives on the challenges and joys of her role as a Catholic, stay-at-home mother, who heads a chapter of the Well-Read Mom, dabbles in social commentary and other writing pursuits, and advocates for the pro-life cause. Despite the inevitable chaos of large family life, Megan is thankful for her lively brood and relishes juggling household responsibilities, babies in diapers, and, of course, a good book. She resides in Noblesville, Indiana, with her husband, Marc, an engineer in the energy industry, and their ten children: five sons and five daughters, ages 15 years to 6 months old.

About Well-Read Mom

In Well-Read Mom, women read more and read well. Our hope is to deepen the awareness of meaning hidden in each woman’s daily life. We long to elevate the cultural conversation and revitalize reading literature from books. If you would like us to help you select worthy reading material, we invite you to join and read along. We are better together! For information on how to start or join a Well-Read Mom group visit our website wellreadmom.com