The Restless Human Heart in the Search for Happiness

Written by Megan Keyser

Yesterday, while driving my lively entourage from school, I entered into a dispute with my twelve-and-a-half-year-old son. Frustrated at his mother’s cruel infringements upon, what I considered, his all-too-free speech, he passionately retorted: “What about the First Amendment?” I could relate to my son’s bristling at limitations upon personal desire. Practically, all it takes is a mother’s encounter with her unruly toddler, wailing in exasperation as a contraband item is loosened from his iron grip to vividly illustrate the universal struggle to tame our desires. From our earliest moments, we consider submission to authority as infringing upon our freedom and, subsequently, our happiness.

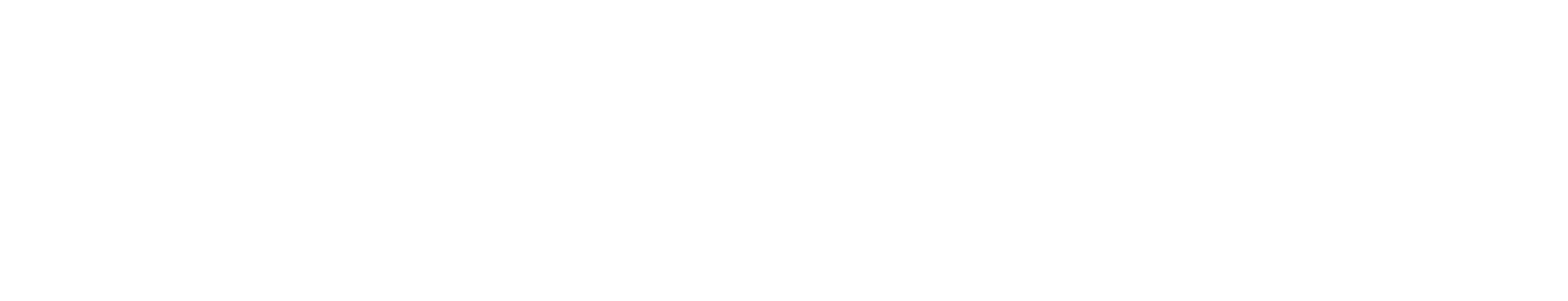

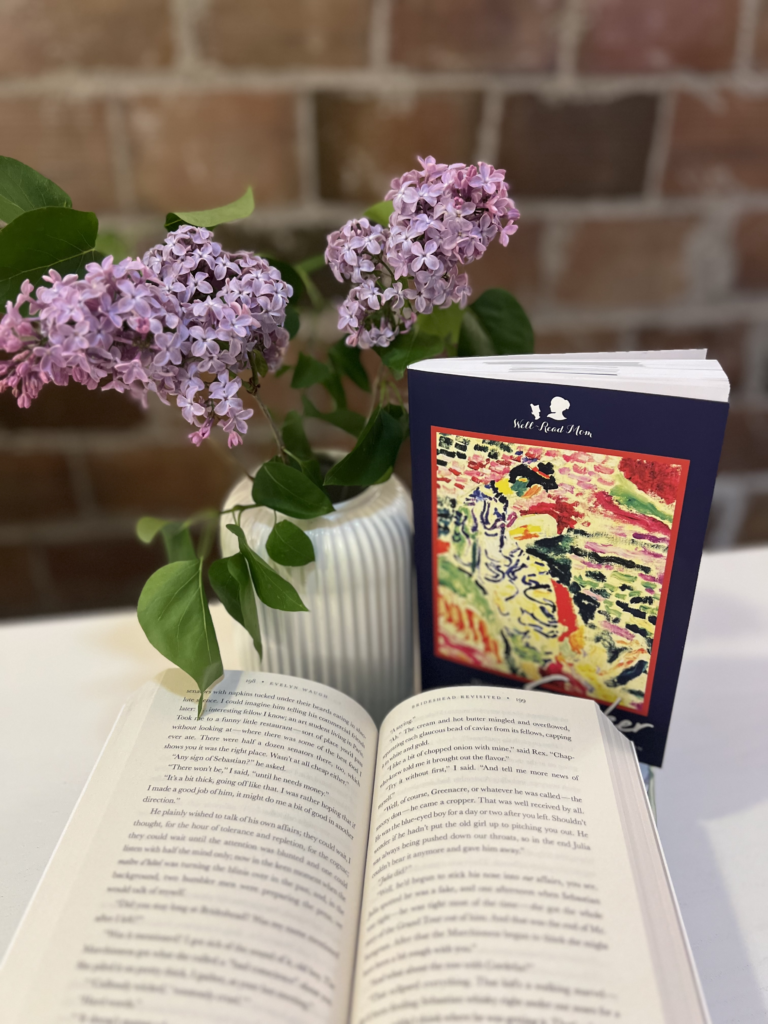

Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited centers on this trouble of the turbulent human heart. It is the story of a 20th-century Catholic family ravaged by incredible hardship. Yet the book possesses a mysteriously indescribable charm. With aching realism, the interior battle of the human heart is masterfully crystalized through the drama’s unfolding. Though all the characters traverse unique struggles, what unites each of them becomes increasingly apparent: they all seek happiness, fulfillment, and purpose.

Yet, for most of the characters, these goals remain elusive, primarily and ironically, due to the debilitating ramifications of personal license. Watching the characters contend with the adverse effects of pursuing one’s desires at the cost of what is right should pause us: How often are we instrumental in our misery and discord? How does our own distaste for restraint paradoxically imprison us?

Like a blissfully ignorant toddler, we run headlong into traffic, then shriek and writhe in our rescuer’s arms when our rush at coveted freedom is thwarted. Yet, like the angry toddler, all we see are the thrills of a fleeting experience being ripped from us—not the danger and pain being carefully averted by one with a farther-reaching perspective.

With limited vision, we grasp glittering idols—illicit love, self-indulgence, or freedom from responsibility—but beneath this insatiable desire for the “right” to do as we wish is a thinly veiled longing for complete happiness. Not the kind of happiness that gives momentary satisfaction but the happiness that allows us to find joy even amid hardships, firmly rooting us in incomprehensible peace.

Charles, even as he enjoys his scandalous love affair with Julia, penetrates this idea that our earthly longings, whether licit or not, are merely futile attempts to snatch at a joy that seems perpetually beyond the here and now: “…perhaps all our loves are merely hints and symbols; vagabond-language scrawled on gateposts and paving-stones along the weary road that others have tramped before us; perhaps you [Julia] and I are types and this sadness which sometimes falls between us springs from disappointment in our search, each straining through and beyond the other, snatching a glimpse now and then of the shadow which turns always a pace or two ahead of us” (348). Despite his passionate ardor for Julia, Charles feels this unsatisfied longing cannot be realized, even in her.

Let us then contrast Charles with Brideshead (Bridey), who seems to possess something his siblings all lack: an inner peace that is so undisturbed that one might call it a “peace which passeth understanding.” Though his family members often seem to be roiled in the torments of emotional upheaval, Bridey remains inexplicably placid. When various characters’ feelings sway their convictions or actions, Bridey is the forthright yet calm speaker of hard truths. Though he may be criticized for bluntly offering the truth, he must also be commended for dispassionately sharing it. He never expresses malice or self-importance in stating this truth, and he never attempts to shame or humble anyone when he shares it. He shares it with a childlike resolution.

Brideshead states moral truth with the same conviction and certainty as someone who attests that the sky is blue. This childlike candor unsettles most of the other characters, taking them completely off guard and stopping them in their wayward tracks. At one point, the cynical, atheistic Charles criticizes Bridey’s unequivocal judgments as rubbish: “D’you know, Bridey, if I ever felt for a moment like becoming a Catholic, I should only have to talk to you for five minutes before being cured. You manage to reduce what seem quite sensible propositions to stark nonsense” (188-189).

While Bridey’s straightforward manner is certainly off-putting to other characters, particularly those without his sense of conviction, his frankness in expressing his thoughts seems to rub many readers the wrong way. Where’s his humanity and sympathy for human foibles? Has he no feeling?

How many times do modern critics say the same about the Church? Where is Her understanding in the face of suffering? Where is her compassion when She speaks against sin? In considering the similarities between Bridey and the Church, this quote seemed particularly apt: “…[Bridey] was usually preposterous yet somehow achieved a certain dignity by his remoteness and agelessness; he was still half-child, already half-veteran; there seemed no spark of contemporary life in him; he had a kind of massive rectitude and impermeability, an indifference to the world, which compelled respect. Though we often laughed at him, he was never wholly ridiculous; at times, he was even formidable” (323-324).

We live in a world where even the most noble seem wary of “rocking the boat” or appearing foolish or irrelevant to others. We skirt around “dangerous” topics, choosing our words cautiously so as not to incite anger or mockery from those who reject our views. We want to make virtue palatable to everyone, so we sometimes fear distinguishing ourselves, lest we look silly, insensitive, or unreasonable. But while we should never offer the truth with meanness or cruelty, perhaps we should imitate Bridey by seeking more extraordinary courage in admitting and sharing the truth. It may seem counterintuitive, but if the rebellious elevation of self and personal pleasure can inflict sorrow, could the meekness required in conforming to God’s Truth be a source of genuine liberation as a solid means of obtaining lasting peace? A wise priest recently told me that meekness is often equated with mere gentleness.

Still, while gentleness is typically a related virtue, true meekness is the willingness to conform one’s will to something greater—even if this conformity exacts a high cost. A warhorse demonstrates meekness each time he follows his master’s commands without hesitation, even if those steps walk him through a shower of cannon fire and bring him immediate pain and suffering because something more significant is at stake than physical or emotional comfort. In our modern world, this submission seems perplexing, as we often equate pleasure with goodness, “But” as Bridey poses, “is there a difference between liking a thing and thinking it good?” (102).

So, what is the path to enduring happiness? The world tells us that happiness is found in self-fulfillment, prestige, and renown and in following the unexamined desires of the heart. Yet, our aim is to become increasingly Christ-like. In that case, what we desire is not always the path to virtue. Of course, we may appear foolish to a world that scoffs at and ridicules moral certitude and self-denial. But if the tale of Brideshead Revisited resonates at all, it should remind us that we are never more imprisoned than when we, “reveling” in a counterfeit “independence,” are slaves to our own narrow interests.

We are never more free than when we conform to the One Whose goodness knows no bounds. The happiest people are not those anxiously searching for something to “like,” flitting from pleasure to pleasure, but those seeking a Magnificence so immense that it eclipses our sufferings and offers us tranquil rest—even as it demands much from us. As Saint Augustine wrote, “Our hearts are restless till they find rest in Thee.”

Megan Keyser

Originally hailing from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Megan is a 2006 Hillsdale College graduate with a degree in Classical Studies. These days, Megan thrives on the challenges and joys of her role as a Catholic, stay-at-home mother, who heads a chapter of the Well-Read Mom, dabbles in social commentary and other writing pursuits, and advocates for the pro-life cause. Despite the inevitable chaos of large family life, Megan is thankful for her lively brood and relishes juggling household responsibilities, babies in diapers, and, of course, a good book. She resides in Noblesville, Indiana, with her husband, Marc, an engineer in the energy industry, and their ten children: five sons and five daughters, ages 15 years to 6 months old.

About Well-Read Mom

In Well-Read Mom, women read more and read well. Our hope is to deepen the awareness of meaning hidden in each woman’s daily life, elevate the cultural conversation, and revitalize reading literature from books. If you would like to have us help you select worthy reading material, we invite you to join and read along with us. We are better together! For information on how to start or join a Well-Read Mom group visit our website wellreadmom.com