The Truths of Motherhood: Reflections on Courage, Grief, and Love

Written By Megan Keyser

“My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness…

2 Corinthians 12: 9-10

Therefore, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and constraints, for the sake of Christ; for when I am weak, then I am strong.”

The funny thing about motherhood is that, before entering this state of life, one cannot possibly grasp the magnitude of the undertaking. No matter how many well-written parenting books we read, no matter how many emphatic relatives opine on this or that aspect of child-rearing, no matter how “prepared” one feels to embark on the journey, the inescapable truth is—from the exalted heights of all-encompassing joy and rapture to the anguishing depths of heartache and desolation—we are all hopelessly unprepared for what lies across the great divide between maidenhood and motherhood.

From the moment we learn we are pregnant—often as we clutch a pregnancy test with shaking hands, watching it transform before our awe-filled eyes—our lives are fundamentally changed. In a moment, our lives link to another life as we begin the thrill motherhood. While we often expect the joys of watching this new life blossom and even anticipate the hard work of late-night feedings, dirty diapers, and increased demands upon our time, we don’t tend to expect the overwhelming fear. We don’t envision the anxieties that will creep into our souls repeatedly. We don’t imagine how our hearts will be torn asunder under the weight of genuine love. We cannot comprehend the cost of fully giving.

And the cost can be excruciating. Before becoming a mother, we might vaguely understand the fog of sleep deprivation—having spent “all-nighters” in high school or college preparing for the next day’s exam—but has that fatigue been accompanied by fearing for another life? Waking to face a day of classes is difficult, but the promise of the weekend serves as a beacon of hope, giving us the resolve to trudge to class, knowing that our restorative destinies were still our own. But what reprieve is there for a mother’s night watches, when children will incessantly beg for breakfast at the earliest hours, and the laundry pile will grow ever higher? Before motherhood, we think we know the depth of anxiety as we await college acceptance letters or the outcome of a job interview. Still, we didn’t realize the dread that fills a mother’s heart when an ultrasound technician utters, “I’m so sorry, but…” and worlds come crashing down.

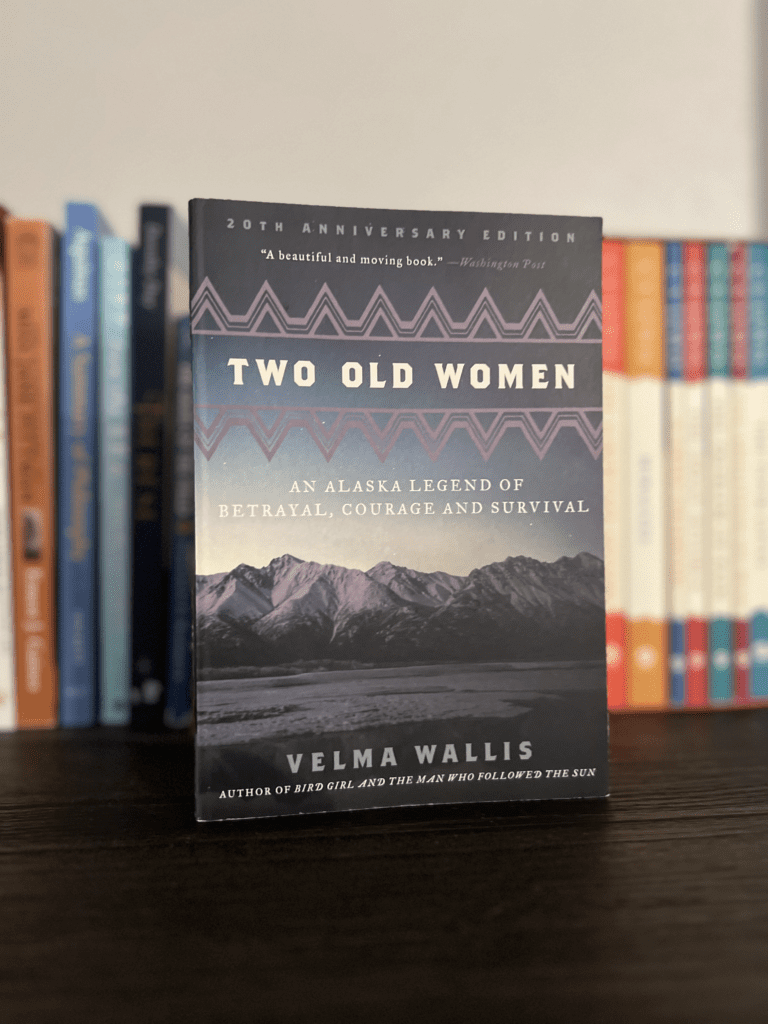

No one tells a new mother how frequently she will be called upon to be courageous, how mind-bending and challenging the circumstances may become, and how, even in the very best of cases, the demands upon her endurance, her fortitude, her mental outlook, and her faith will be maddeningly challenged. In many ways, Velma Wallis’ Two Old Women mirrors the struggle felt by mothers as she chronicles the desolation, the loneliness, and the discomforts of Sa’ (Star) and Ch’idzigyaak (Chickadee), two ancients from an Athabascan Native American tribe, who abruptly discover themselves alone, facing what appears to be certain death, after their fellow tribesmen cast them off. Gripped with fear and consumed by outraged resentment, the women battled the elements, the hunger, and the isolation, facing hardships almost incomprehensible to the modern mind. However, most striking to me was not how they handled the extreme Alaskan winter but how they conquered the trepidation and panic in themselves.

Though I have been fortunate and blessed to experience much happiness in my mothering journey, there have been innumerable times when I have felt the walls caving in and snatched at shreds of hope. Most of these moments surface as I face the daily grind so familiar to mothers, particularly those with numerous children, who face the unique challenges of large families: mental and physical “mountains” comprised of seemingly limitless “to-do” lists, a lack of quiet and order, and very little sleep or personal time. Motherhood is a life lived in direct conflict with the contemporary ideal of pursuing personal ambitions and seeking ease and calm; it is a life oriented toward hard work and offered (hopefully) with great love. But recently, that daily grind has also paired with personal tragedy and disappointment. I have found myself overcome by the swells of deep, uncharted wells of grief and loss. From the depths, Ch’idzigyaak’s sentiments reverberate in my head: “She did not want to face the day.”

Over Christmas, we lost our eleventh child in a miscarriage. Though I imagined I had steeled myself against the heartache by preparing myself for the distinct possibility of loss, when our tiny baby’s passing was confirmed, I was unprepared for the waves of emotion and devastation that wracked my heart. Sitting alone in my car on the afternoon of Christmas Eve, I felt betrayed by God: Why had He allowed this to happen—especially now, at what was supposed to be a joyous time? And in my anguish, I remember screaming, at the top of my lungs, “I hate this!” before succumbing to a deluge of tears.

I met the following weeks with ever-vacillating emotions and confusion of feelings that only made ordinary life seem increasingly oppressive. Suddenly, facing household clutter, cranky preschoolers, and mischievous toddlers seemed insurmountable. Like Sa, like many burned-out, frustrated, and overwhelmed mothers, I felt my energy completely ebb, pushed to my absolute emotional limits: “Without meaning to, Sa’ let out a painful moan, and she felt a great urge to cry. She hung her head, defeated by all they had been through these past few days, and the cold made her feel even more despair. As much as she wanted to, her body would not move” (page 42). Though it may seem dramatic, I lamented the perpetually disorganized state of my house and my inability to keep up with the pace of deadlines and activities. My family’s needs and my own were disappointed at not fully being able to pursue my aspirations and goals, and I wondered: Why does this all feel so meaningless, so fruitless? Through tears, I told my husband my will to preserve was faltering. I felt the way Ch’idzigyaak must have felt when she reasoned: “Perhaps it was not meant for them to go on. Perhaps the young ones were right—she and Sa’ were fighting the inevitable. It would be easy for them to snuggle deeper into the warmth of their fur clothing and fall asleep. They would not have to prove anything to anyone anymore” (43).

However, life often has ways of forcing one into action, even when one thinks she cannot give another bit of herself. Paradoxically, the day after my tear-filled emotional collapse, our eight-year-old was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes. Again, I felt the earth sink beneath my feet, and I held my tears and my breath as I heard the hospital staff relate what I already knew: our lives had changed forever. Another level of complexity, of strain, of worry, had begun. “God, I am no saint. I am no hero. I can’t do this.” And I felt my spirit crumple.

But I must do this. We must do this. My husband and I must because our daughter’s life depends upon it. The steps might be arduous, and the path might be (in fact, it is) lifelong, but we must travel the road because that is the cost of loving, living, and entirely giving. Once more, the words of Sa’ rang in this recognition: “If we are going to die, my friend, let us die trying, not sitting” (14). So, even when I thought I couldn’t go another step, I am asked to give more to demonstrate my love for this beautiful, vulnerable child my husband and I have created. The Lord asks me to set aside my comforts and surrender to the raw, agonizing demands of sacrificial love that open wide the human heart, stretching it to the bounds of mortal comprehension and exposing its fragility. In The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis wrote: “To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.”

As mothers, our nerve may fail us more times than we would like to admit. We may feel utterly inadequate to the challenge ahead, but if, like Sa’ and Ch’idzigyaak, we continually remind ourselves of what is at stake—namely, our eternal life and the flourishing of our families, friends, and community—and we increasingly turn to God and those He has placed in our lives to bolster us in moments of doubt and uncertainty, we may accomplish more than we ever thought possible, even though those accomplishments might remain hidden to the eyes and only fully recognized by the heart. By giving of ourselves in motherhood, even when we feel we have exhausted every reserve of strength and courage we possess, we might “[learn] that from hardship, a side of people emerge[s] that they had not known…[they] whom they thought to be the most helpless and useless had proven themselves to be strong” (115).

Megan Keyser

Originally hailing from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Megan is a 2006 Hillsdale College graduate with a degree in Classical Studies. These days, Megan thrives on the challenges and joys of her role as a Catholic, stay-at-home mother, who heads a chapter of the Well-Read Mom, dabbles in social commentary and other writing pursuits, and advocates for the pro-life cause. Despite the inevitable chaos of large family life, Megan is thankful for her lively brood and relishes juggling household responsibilities, babies in diapers, and, of course, a good book. She resides in Noblesville, Indiana, with her husband, Marc, an engineer in the energy industry, and their ten children: five sons and five daughters, ages 15 years to 6 months old.

About Well-Read Mom

In Well-Read Mom, women read more and read well. Our hope is to deepen the awareness of meaning hidden in each woman’s daily life, elevate the cultural conversation, and revitalize reading literature from books. If you would like to have us help you select worthy reading material, we invite you to join and read along with us. We are better together! For information on how to start or join a Well-Read Mom group visit our website wellreadmom.com